Greene the Union Show Art Front May 1936

| Popular Forepart Forepart populaire | |

|---|---|

| Leader | Maurice Thorez Léon Blum Camille Chautemps Marcel Déat |

| Founded | 1936 (1936) |

| Dissolved | 1938 (1938) |

| Preceded by | Lefts Dare |

| Headquarters | Paris |

| Ideology | Anti-fascism Internal factions: • Democratic socialism • Social republic • Social liberalism • Communism • Anti-clericalism |

| Political position | Left-wing |

| Colours | Red |

| |

The Popular Forepart (French: Forepart populaire) was an brotherhood of French left-fly movements, including the communist French Communist Political party (PCF), the socialist French Department of the Workers' International (SFIO) and the progressive Radical-Socialist Republican Party, during the interwar period. Three months subsequently the victory of the Castilian Popular Front, the Popular Front end won the May 1936 legislative election, leading to the germination of a government get-go headed past SFIO leader Léon Blum and exclusively composed of republican and SFIO ministers.

Blum's regime implemented various social reforms. The workers' movement welcomed this electoral victory by launching a full general strike in May–June 1936, resulting in the negotiation of the Matignon Agreements, one of the cornerstones of social rights in France. All employees were assured a ii-calendar week paid vacation, and the rights of unions were strengthened. The socialist movement'due south euphoria was apparent in SFIO member Marceau Pivert's "Tout est possible!" (Everything is possible). However, the economy continued to stall, with 1938 production still not having recovered to 1929 levels, and higher wages had been neutralized by inflation. Businessmen took their funds overseas. Blum was forced to stop his reforms and devalue the franc. With the French Senate controlled past conservatives, Blum fell out of ability in June 1937. The presidency of the chiffonier was then taken over past Camille Chautemps, a Radical-Socialist, but Blum came back every bit President of the Council in March 1938, before being succeeded past Édouard Daladier, some other Radical-Socialist, the next calendar month. The Pop Front end dissolved itself in autumn 1938, confronted by internal dissensions related to the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), opposition of the right-wing, and the persistent effects of the Great Depression.

Subsequently one yr of major activity, it lost its spirit by June 1937 and could only temporize equally the European crisis worsened. The Socialists were forced out; only the Radical-Socialists and smaller left-republican parties were left. It failed to live upwards to the expectations of the left. The workers obtained major new rights, but their 48 percent increment in wages was offset by a 46 percent rise in prices. Unemployment remained high, and overall industrial production was stagnant. Manufacture had great difficulty adjusting to the imposition of a 40-hr workweek, which acquired serious disruptions while France was desperately trying to grab up with Federal republic of germany in military production. France joined other nations and bitterly disappointed many French leftists in refusing to aid the Castilian Republicans in the Spanish Ceremonious War, partly because the right threatened another civil war in France itself.

Background [edit]

There are various reasons for the formation of the Popular Forepart and its subsequent electoral victory, including the economic crisis caused by the Not bad Low, which affected France starting in 1931, fiscal scandals and the instability of the Chamber of Deputies elected in 1932 that had weakened the ruling parties, the rise of Adolf Hitler in Nazi Federal republic of germany, the growth of violent far-right leagues in French republic and in general of fascist-related parties and organisations (Marcel Bucard'southward Mouvement franciste, which was subsidised past Italian leader Benito Mussolini, Neo-Socialism etc.)

The elections of 1932 had resulted in a victory for the two largest parties of the left, the Marxist SFIO and the Radical-Socialist PRRRS, too equally several smaller parties ideologically close to Radicalism (an electoral pact known every bit the Dare des Gauches); the Communist Party had run on its own, accusing the Socialists of social-fascism and opposing the subsequent centre-left governments. Withal, major differences between the SFIO and PRRRS prevented them from forming a cabinet together, as all had expected, leaving France governed by a serial of short-lived cabinets formed exclusively of the six Radical parties.

SFIO demonstration in response to the 6 February 1934 crisis. A sign reads "Down with fascism"

The Socialist Political party reliably granted its conviction to these cabinets but fundamentally disagreed with their upkeep cuts, and the various pocket-size liberal centre-correct parties who agreed with the upkeep cuts refused to support centre-left governments in which they were not represented. With government paralyzed, tensions grew greater and greater both betwixt the dissimilar parties in parliament and within public opinion. The tensions finally erupted into the infamous 6 February 1934 crisis in which massive riots by authoritarian paramilitary leagues caused the collapse of the Cartel. The Radical-Socialists and other republican centre-left parties accepted entry into a government dominated past the center-correct (the liberal bourgeois Democratic Alliance) and hard correct (the Catholic bourgeois Republican Federation). The support by extreme-right paramilitaries for the National Unity government alarmed the left, which feared that plans to reform the constitution would atomic number 82 to the abandonment of parliamentary government for an disciplinarian regime, equally had recently occurred in other European democracies.

The idea of a "Popular Front" therefore came simultaneously from three directions:

- The frustration felt past many moderate Socialists and left-fly Radical-Socialists at the collapse of their previous attempts at regime and an increasing desire to rebuilt that coalition on a stronger basis to combat the economical crunch of the Smashing Depression

- The left-wing view that the half dozen February 1934 riots had represented a deliberate attempt by the French far correct for a coup d'état against the Republic (this idea is now discredited by historians)

- The Comintern'due south alarm at the increased popularity of fascist and authoritarian correct-fly regimes in Europe, and decision to abandon its hostile position towards social-democracy and parliamentarianism (run into Third Flow) in favour of the "Popular Forepart" position. This advocated an alliance with the social-democrats and authentically democratic middle-class republicans against the greater threat of the far-correct.

Thus, antifascism became the club of the day for a growing number of Communists, Socialists and Republicans equally a result of a convergence of influences: the collapse of the middle-left coalition of 1932, the fear of the consequences of the 1934 riots and the broader European policy of the Comintern.[1] Maurice Thorez, secretary general of the SFIC, was the starting time to call for the formation of a "Popular Front", first in the party printing organ L'Humanité in 1934 and so in the Bedroom of Deputies. The Radical-Socialists were at the fourth dimension the largest political party in the Chamber, and had oftentimes been the dominant party of regime during the second half of the 3rd Republic.

Beside the three main left-fly parties, Radical-Socialists, SFIO and PCF, the Popular Forepart was supported past several other parties and associations.

These included several ceremonious social club organisations, main amidst whom were:

- The Confédération générale du travail (CGT) or General Confederation of Labour, a syndicalist merchandise-union confederation distinct from the Socialist and Communist parties;

- The Ligue des droits de fifty'homme (LDH) or League of Human Rights, a civil rights watchdog formed during the Dreyfus Matter;

- The Movement Against State of war and Fascism, a left-fly anti-war association that fell within the Communist sphere of influence;

- The Comité de vigilance des intellectuels antifascistes (CVIA) or Vigilance Committee of Antifascist Intellectuals, a watchdog created in 1934 to organise resistance against a far-right takeover of the democratic regime.

The Communist, Socialist and Radical-Socialist parties were also joined by several smaller parties, by and large formed by dissidents who in previous years had exited the main iii parties:

- The Socialist Republican Union (USR), a social-democratic republican party led by Paul Ramadier, Marcel Déat and Joseph Paul-Boncour. This had been formed past the fusion of the SFIO's right-wing with the left-wing of the heart-grade republicans;

- The Political party of Proletarian Unity (PUP), a dissident Leninist party created in 1930 and opposed both to social commonwealth and to the Third International;

- The Frontist Party (PF), a small anti-fascist splinter of the Radical-Socialist Party formed by Gaston Bergery in 1933;

- The Parti radical-socialiste Camille Pelletan (PRS-CP), a small anti-fascist splinter of the Radical-Socialist Political party formed in May 1934 by Gabriel Cudenet;

- The Parti de la Jeune République (PJR) or Young Commonwealth party, a small Catholic anti-war party formed by Marc Sangnier;

May 1936 elections and the formation of the Blum government [edit]

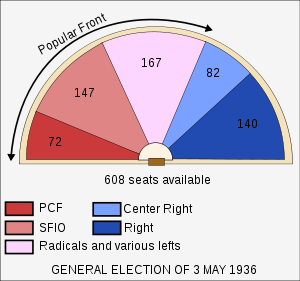

The Popular Forepart won the full general ballot of 3 May 1936, with 386 seats out of 608. For the first time, the Socialists won more seats than the Radical-Socialists, and the Socialist leader, Léon Blum, became the first Socialist Prime Minister of France and the first Jew to hold that function. The first Popular Front cabinet consisted of 20 Socialists, thirteen Radical-Socialists and two Socialist Republicans (there were no Communist Ministers) and, for the commencement time, included three women (who were then not able to vote in France).[ii]

The members of the Pop Front parties too small to class their ain parliamentary grouping (the PUP, PF, PRS-CP and PJR) joined with several independents to sit together as the Independent Left (Gauche indépendante) parliamentary conclave.[3]

In regime [edit]

Labor laws [edit]

Through the 1936 Matignon Accords, the Popular Front authorities introduced new labor laws[4] that did the post-obit:

- created the right to strike

- created collective bargaining

- enacted the constabulary mandating 12 days (two weeks) of paid annual leave for workers

- enacted the law limiting the working week to forty hours; Overtime was prohibited

- raised workers' wages (fifteen% for the lowest-paid and seven% for the relatively well-paid)

- stipulated that employers would recognise shop stewards

- ensured that there would be no retaliation against strikers

The authorities sought to carry out its reforms as rapidly as possible. On 11 June, the Bedchamber of Deputies voted for the forty-60 minutes workweek, the restoration of ceremonious servants' salaries, and two weeks' paid holidays, past a majority of 528 to 7. The Senate voted in favour of these laws within a week.[3]

Domestic reforms [edit]

The Blum administration democratised the Banking concern of France by enabling all shareholders to nourish meetings and fix up a new council with more than representation from authorities. By mid-August the parliament had passed:

- the creation of a national Office du blé (Grain Lath or Wheat Role, through which the authorities helped to market agricultural produce at off-white prices for farmers) to stabilise prices and curb speculation

- the nationalisation of the arms industries

- loans to small and medium-sized industries

- the raising of the compulsory school-leaving age to fourteen years

- measures against illicit price rises

- a major public works program

The legislative pace of the Pop Forepart government meant that before parliament went into recess, information technology had passed 133 laws within the space of 73 days.

Other measures carried out by the Popular Front end government improved the pay, pensions, allowances, and taxes of public-sector workers and ex-servicemen. The 1920 sales tax, opposed by the Left as a tax on consumers, was abolished and replaced by a production tax, which was considered to be a taxation on the producer instead of the consumer. The government also made some administrative changes to the civil service, such every bit a new director-full general for the Paris police and a new governor for the Bank of France. In addition, a secretariat for sports and leisure was established, and opportunities for the children of workers and peasants in secondary education were increased. In 1937, careers guidance classes (classes d'orientation) were established in some lycées every bit a ways of helping pupils to brand a amend option of their subsequent course of secondary schooling. Secondary education was made free to all pupils; previously, it had been closed to the poor, who were unable to afford to pay tuition.

In aviation, a decree in December 1936 established a psycho-physiological service for military aviation "with the job of centralising the study of the adaptation of the human being organisation to the optimum utilisation of aeronautical fabric." A Prescript of 12 July 1936 extended compensation to encompass diseases contracted in sewers, skin diseases due to the action of cement, dermatitis due to the action of trichloronaphthaline (acne), and cutaneous and nasal ulceration from potassium bichromate. An Act of Baronial 1936 extended to workers in full general supplementary allowances that had previously been confined to workers injured in accidents prior to 9 Jan 1927. An society dealing with rescue equipment in mines was issued on 19 August 1936, followed past 2 orders concerning packing and caving on 25 February 1937. In relation to maritime transport, a Decree of 3 March 1937 issued instructions concerning prophylactic.[5] A decree of 18 June 1937 promulgated the Convention "concerning the marking of the weight on heavy packages transported past vessels which was adopted by the International Labour Conference at Geneva in 1929".[6]

In Oct 1936, the government ratified a League of Nations Convention dating back to October 1933, which granted Nansen refugees "travel and identity documents that afforded them protection against arbitrary refoulement Italic textand expulsion."[7] The Walter-Paulin Police force of March 1937 set standards for apprenticeship teachers and ready a corps of salaried inspectors,[8] while a decree of June 1937 decided on the "creation of the workshop schools, close to schools [...] that should awaken the skills and curiosity of students, open more to life school work, let them know about the local history and geography."[9] In June 1937, vacation camps ('colonies') received a nationwide public statute through their first comprehensive country regulation.[10]

An act of 26 Baronial 1936 that amended the social insurance scheme for commerce and industry raised the maximum daily maternity benefit from eighteen to 22 francs, and an order of 13 February 1937 prescribed a special sound bespeak for road-rail coaches. Improvements were made in unemployment allowances, and an Human action of Baronial 1936 increased the rate of pensions and allowances payable to miners and their dependents. In August 1936, regulations extending the provisions of the Family Allowances Human action to agronomics were signed into law. A decree was introduced that same calendar month for the inspection of subcontract dwellings, and at the beginning of January 1937, an Informational Committee on Rents was appointed by decree. To promote turn a profit-sharing, an Act of January 1937 (that regulated the working of the State mines, the Alsatian potash mines, and the potash manufacture), provided that 10% of the net yield of the undertaking "must be fix aside, to be used, at to the lowest degree to the extent of one half, to enable the staff to share in the profits of the manufacture."[five]

Blum persuaded the workers to accept pay raises and go dorsum to work, ending the massive wave of strikes that disrupted production in 1936. Wages increased sharply, in two years the national boilerplate was up 48 pct. However aggrandizement too rose 46%.[11] The imposition of the 40-hour week proved highly inefficient, as manufacture had a difficult time adjusting to information technology. At the end of 40 hours, a shop or pocket-size factory had to shut downwards or supervene upon its best workers; unions refused to compromise on this issue. The limitation was concluded by the Radicals in 1938.[12] The economic confusion hindered the rearmament endeavour; the rapid growth of German language armaments alarmed Blum. He launched a major program to speed up artillery product. The toll forced the abandonment of the social reform programs that the Popular Front had counted heavily on.[thirteen]

Far correct [edit]

Blum dissolved the far-right fascist leagues. In plough, the Popular Front was actively fought by right-fly and far-right movements, which ofttimes used antisemitic slurs against Blum and other Jewish ministers. The Cagoule far-right group even staged bombings to disrupt the regime.[14]

Spanish Civil War [edit]

The Spanish Civil War broke out in July 1936 and deeply divided the government, which tried to remain neutral. The French left massively supported the Republican government in Madrid, and the right mostly supported the Nationalist insurgents, some even threatening to bring the state of war to France. Blum's cabinet was also deeply divided. Fear of the war spreading to France was ane cistron that made him decide on a policy of non-intervention. He collaborated with Great britain and 25 other countries to formalize an agreement against sending any munitions or volunteer soldiers to Kingdom of spain.[xv]

The air minister defied the cabinet and secretly sold warplanes to Madrid. Jackson concludes that the French regime "was nearly paralyzed past the menace of Civil State of war at home, the German danger away, and the weakness of her own defenses."[sixteen] The Republicans in Spain plant themselves increasingly on the defensive, and over 500,000 political refugees crossed the border into France, where they lived for years in refugee camps.[17]

Collapse [edit]

After 1937, the precarious coalition went into its death throes with ascension extremism on left and correct, besides as biting recriminations.[eighteen] The economy remained brackish, and French policy became helpless in the face up of rapid growth of the German threat.

By 1938, the Radicals had taken control and forced the Socialists out of the chiffonier. In tardily 1938, the Communists broke with the coalition by voting confronting the Munich agreement, in which the Pop Front had joined with the British past handing over role of Czechoslovakia to Germany. The regime denounced the Communists as warmongers, who provoked large-scale strikes in belatedly 1938. The Radical government crushed the Communists and fired over 800,000 workers. In result, the Radical Political party stood alone.[19]

Cultural policies [edit]

Radical cultural ideas came to the fore in the era of the Popular Front end and frequently were explicitly supported by the governments, every bit in the 1937 Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne.[20]

An "art for the masses" movement flourished, led past efforts of three of the most influential art magazines to legitimize a visual imagery: Cahiers d'art, Minotaure, and Verve. The prevailing leftist anti-capitalist discourse against social inequality was a feature of the Popular Front cultural policy.[21]

The authorities proposed a draft law concerning intellectual belongings right, based on a new philosophy that did not consider the author equally an "possessor" (propriétaire) but as an "intellectual worker" (travailleur intellectuel). Notwithstanding, the draft failed to pass.[22]

New communist positions [edit]

The new cross-class coalition of the Popular Forepart forced the Communists to accept some bourgeois cultural norms that they had long ridiculed.[23] These included patriotism, the veterans' cede, the honor of existence an army officer, the prestige of the bourgeois, and the leadership of the Socialist Party and the parliamentary Republic. Above all, the Communists portrayed themselves as French nationalists. Immature Communists dressed in costumes from the revolutionary period and the scholars glorified the Jacobins as heroic predecessors.[24]

The Communists in the 1920s saw the need to mobilize young women but saw them as auxiliaries to male person organizations. The 1930s had a new model of a dissever-merely-equal role for women. The political party set the Marriage des Jeunes Filles de France (UJFF) to appeal to young working women through publications and activities that were geared to their interests. The party discarded its original notions of Communist femininity and female political activism as a gender-neutral revolutionary. It issued a new model more attuned to the mood of the late 1930s and i more adequate to the middle course elements of the Pop Front. It now portrayed the platonic young Communist woman as a paragon of moral probity with her commitment to wedlock and motherhood and gender-specific public activism.[25]

Sports and leisure [edit]

With the 1936 Matignon Accords, the working course gained the right to 2 weeks' vacation a year for the first fourth dimension. This signaled the beginning of tourism in France. Although beach resorts had long existed, they had been restricted to the upper grade. Tens of thousands of families who had never seen the sea before at present played in the waves, and Léo Langrange arranged around 500,000 discounted rail trips and hotel accommodation on a massive calibration. All the same, the Popular Front's policy on leisure was limited to the enactment of the two-calendar week vacation. While this mensurate was idea of equally a response to workers' alienation, the Popular Front end gave Lagrange (SFIO), named Under-Secretary for Sports and the arrangement of Leisure, responsibility for organizing the use this leisure time with priority to sports.

The fascist conception and utilise of sport as a means to an end contrasted with the SFIO's official opinion, which had ridiculed sports as a bourgeois and reactionary activity. However, confronted with an increasing possibility of war with Nazi Frg and afflicted by the scientific racist theories of the fourth dimension, which were common beyond the fascist parties, the SFIO began to modify its ideas concerning sports during the Popular Front, because its social reforms permitted to the workers' to participate in such leisure activities and besides because of the increasing risks of a confrontation with Nazi Germany, peculiarly later the March 1936 remilitarization of the Rhineland. That new sign of German'due south revisionism towards the atmospheric condition of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles violated the 1925 Locarno Treaties, which had been reaffirmed in 1935 by France, Britain and Italy, allied in the Stresa Front. That led parts of the SFIO in supporting a conception of sport used as a training field for future conscription and, eventually, war.

The complex situation did non stop Lagrange from property fast to an upstanding formulation of sports that rejected fascist militarism and indoctrination, scientific racist theories and the professionalisation of sports, which he opposed as an elitist formulation that ignored the main popular aspect of sport. He considered that sport should aim for the fulfilment of the personality of the individual. Thus, Lagrange stated, "It cannot be a question in a democratic country of militarizing the distractions and the pleasures of the masses and of transforming the joy skillfully distributed into a means of not thinking." Léo Lagrange further declared in 1936:

"Our simple and human goal is to allow the masses of French youth to find in the do of sport, joy and health and to build an organization of the leisure activities so that the workers can discover relaxation and a reward to their difficult labour."

Langrange too explained:

"Nosotros want to make our youth healthy and happy. Hitler has been very clever at that sort of thing, and there is no reason why a democratic government should not do the same."

Thus, as shown by the bureaucracy of the ministers, which placed the sub-secretarial assistant of sport nether the authority of the Government minister of Public Health, sport was considered above all as a public health issue. From this principle, it was only one pace to relating sport to the "degeneration of the race" and other scientific racist theories. It was done by Georges Barthélémy, deputy of the SFIO, who declared that sports contributed to the "improvement of relations between capital and labour, henceforth to the elimination of the concept of class struggle" and that they were a "ways to foreclose the moral and physical degeneration of the race."

Such corporatist conceptions had led to the neo-socialist motility, whose members had been excluded from the SFIO on 5 November 1933. However, scientific racist positions were upheld within the SFIO and the Radical-Socialist Party, who supported colonialism and constitute in this soapbox a perfect ideological alibi to justify colonial rule. After all, Georges Vacher de Lapouge (1854–1936), a leading theorist of scientific racism, had been a SFIO member, although he was strongly opposed to the "Teachers' Republic" (République des instituteurs) and its meritocratic ideal of individual advancement and fulfillment through education, a Republican platonic founded on the philosophy of the Enlightenment.

1936 Olympic Games [edit]

The International Olympic Commission chose Berlin over Barcelona for the 1936 Olympic Games. In protest against holding the event in a fascist land, the Spanish Pop Front, decided to organize rival games in Barcelona, nether the name People's Olympiad. Blum's regime at first decided to accept part in it, on insistence from the PCF, but the games were never held because the Spanish Civil War broke out.

Léo Lagrange played a major office in the co-organisation of the People's Olympiad. The trials for these Olympiads proceeded on iv July 1936 in the Pershing stadium in Paris. Through their guild, the FSGT, or individually, ane,200 French athletes were registered with these anti-fascist Olympiads.

Nevertheless, Blum finally decided non to vote for the funds to pay the athletes' expenses. A PCF deputy alleged: "Going to Berlin is making oneself an accomplice of the torturers...." Nonetheless, on ix July, when the whole of the French correct wing voted for the participation of France in the Olympic Games of Berlin, the left fly (PCF included) abstained. The movement passed, and France participated at Berlin.

1937 Million Franc Race [edit]

In 1937, the Popular Front end organized the Million Franc Race to induce automobile manufacturers to develop race cars capable of competing with the German language Mercedes-Benz and Automobile Union racers of the time, which were backed by the Nazi government as part of its sports policy. Hired by Delahaye, René Dreyfus beat Jean-Pierre Wimille, who ran for Bugatti. Wimille would afterwards take part in the Resistance. The next yr, Dreyfus succeeded in overwhelming the legendary Rudolf Caracciola, and his 480 horsepower (360 kW) Silver Arrow at the Pau K Prix, becoming a national hero.[26]

Colonial policy [edit]

The Popular Forepart initiated the 1936 Blum-Viollette proposal, which was supposed to grant French citizenship to a minority of Algerian Muslims. Opposed both by colons and by Messali Hadj's pro-independence political party, the project was never submitted to the National Assembly's vote and was abandoned.[27]

Legacy [edit]

Many historians gauge the Popular Front end to be a failure in terms of economics, foreign policy and long-term stability. "Disappointment and failure," says Jackson, "was the legacy of the Popular Front."[18] [28] Philippe Bernard and Henri Dubief ended, "The Front end Populaire came to grief through its ain economical ineffectiveness and considering of external pressures over which it had no command."[29] In that location is full general agreement that at starting time it created enormous excitement and expectation on the left, but in the end, it failed to live upwards to its hope.[30] There is also general understanding, that the Popular Front provided a set of lessons and fifty-fifty an inspiration for the future.[31] It began a process of government intervention into economic affairs that grew chop-chop during the Vichy and postwar regimes into the modernistic French welfare state.[32]

Charles Sowerwine argues that the Popular Front was above all a coalition confronting fascism, and it succeeded in blocking the inflow of fascism in France until 1940. He adds that it "failed to brand the great changes its supporters anticipated and left many ordinary French people deeply disillusioned."[33]

The reasons for the failure continue to be debated. Many historians arraign Blum for existence also timid and thereby dissolving the revolutionary fervor of the workers.[34] [35] [36] MacMillan says that Blum "Lacked the inner convictions that he was the man to resolve the country's problems by assuming and imaginative leadership," leading him to avert a showdown with the financial powers, and forfeiting the support of the working course.[37]

Other scholars blame the complex coalition of Socialist and Radicals, who never really agreed on labor policy.[38] [39] Others point to the Communists, who refused to turn the full general strike into a revolution, as well as their refusal to join the government. From the perspective of the far left, "The failure of the Pop Forepart regime was the failure of the parliamentary system," says Allen Douglas.[forty] [41]

Economical historians indicate to numerous bad financial and economic policies, such as delayed devaluation of the franc, which fabricated French exports uncompetitive.[42] Economists specially consider the bad furnishings of the 40-hour week, which made overtime illegal, forcing employers to cull whether end work or to replace their best workers with inferior and inexperienced workers when 40 hours had been reached. More than generally, the argument is made that France could non afford the labor reforms in the face up of poor economical conditions, the fears of the business organization community, and the threat of Nazi Germany.[43] [44] The forty hour calendar week was particularly problematic in light of German weapons production - French republic was trying to compete with a nation which non simply had a larger population but one which was working fifty to sixty 60 minutes piece of work weeks. The limits on working hours particularly express aircraft product, weakening French aviation and thus encouraging concessions at the Munich Understanding.[45]

Composition of Léon Blum's government (June 1936 – June 1937) [edit]

- "SFIO" refers to membership to the French Department of the Workers' International, while RAD refers to membership to the Radical-Socialist Political party. The French Communist Party (PCF) restricted itself to a "back up without participation" of the authorities (pregnant it took part to the parliamentary majority but did not have any ministers). The Popular Front authorities coincides with its leadership past Léon Blum, from 5 June 1936 to 21 June 1937.

- Léon Blum (SFIO), President of the Quango

- Édouard Daladier (RAD), Vice-President of the Council and Government minister of War and of National Defence

- Camille Chautemps (RAD) – Minister of State

- Paul Faure (SFIO) – Government minister of State

- Maurice Viollette (USR) – Government minister of State

- Yvon Delbos (RAD), Minister of Foreign Affairs

- Roger Salengro (SFIO), Minister of Interior

- Vincent Auriol (SFIO), Minister of Finances

- Charles Spinasse (SFIO), Minister of National Economic system

- Marc Rucart (RAD), Minister of Justice

- Jean-Baptiste Lebas (SFIO), Minister of Labour

- Alphonse Gasnier-Duparc – Minister of Marine

- Pierre Cot (RAD) – Government minister of Air

- Jean Zay (RAD) – Minister of National Education

- Albert Rivière (SFIO) – Minister of Pensions

- Georges Monnet (RAD) – Government minister of Agriculture

- Marius Moutet (SFIO) – Minister of Colonies

- Albert Bedouce (SFIO) – Minister of Public Works

- Henri Sellier (SFIO) – Minister of Public Health

- Robert Jardillier (SFIO) – Government minister of Posts, Telegraphs, and Telephones (PTT)

- Paul Bastid (RAD) – Minister of Commerce

- Léo Lagrange (SFIO), Nether-Secretary of State for Leisure and Sports (under the dominance of the Minister of Public Health)

- On 18 November 1936, Marx Dormoy (SFIO) replaced Roger Salengro at the Interior, following the latter's suicide.

Encounter also [edit]

- Popular Front in Senegal

- Matignon Accords (1936)

- History of the Left in French republic

References [edit]

- ^ Brian Jenkins, "The Six Fevrier 1934 and the 'Survival' of the French Commonwealth," French History (2006) 20#3 pp 333-351.

- ^ Julian T. Jackson, Popular Front in France: Defending Democracy 1934–1938 (1988)

- ^ a b Jackson, Popular Front in French republic: Defending Democracy 1934–1938 (1988)

- ^ Adrian Rossiter, "Pop Front end economic policy and the Matignon negotiations." Historical Journal 30#three (1987): 663-684. in JSTOR Archived xiv May 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b http://www.ilo.org/public/libdoc/ilo/P/09614/09614%281936-1937%29.pdf[ bare URL PDF ]

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived re-create every bit championship (link) - ^ Caestecker, F.; Moore, B. (2010). Refugees From Nazi Frg and the Liberal European States. Berghahn Books. p. 62. ISBN9781845457990 . Retrieved three March 2017.

- ^ Solar day, C. (2001). Schools and Work: Technical and Vocational Teaching in France Since the Third Commonwealth. MQUP. p. 59. ISBN9780773568952 . Retrieved iii March 2017.

- ^ http://eduscol.education.fr/cid45998/enseigner-les-territoires-de-la-proximite [ permanent dead link ] -quelle-place-pour-l-enseignement-du-local- .html

- ^ Downs, L.L. (2002). Childhood in the Promised Country: Working-Class Movements and the Colonies de Vacances in France, 1880–1960. Duke University Press. p. 196. ISBN9780822329442 . Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ Maurice Larkin, France since the pop front end: government and people, 1936–1996 (1997) pp. 55-57

- ^ Jackson (1990). The Popular Forepart in French republic: Defending Democracy, 1934-38. pp. 111, 175–76. ISBN9780521312523.

- ^ Martin Thomas, "French Economic Affairs and Rearmament: The Beginning Crucial Months, June–September 1936". Journal of Contemporary History 27#4 (1992) pp 659–670 in JSTOR Archived 14 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Geoffrey Warner, "The Cagoulard Conspiracy" History Today (July 1960) ten#0 pp 443-450

- ^ George C. Windell, "Leon Blum and the Crisis over Spain, 1936", Historian (1962) 24#four pp 423–449

- ^ Gabriel Jackson, The Spanish Democracy in the Civil State of war, 1931–1939 (1965) p 254

- ^ Louis Stein, Beyond Expiry and Exile: The Spanish Republicans in France, 1939–1955 (1980)

- ^ a b Bernard and Dubief (1988). The Decline of the Third Democracy, 1914-1938. pp. 328–33. ISBN9780521358545.

- ^ Charles Sowerwine, France since 1870: Culture, Society and the Making of the Republic (2009) pp 181–82

- ^ Dudley Andrew, and Steven Ungar, Pop Front Paris and the Poetics of Civilization (2005)

- ^ Chara Kolokytha, "The Fine art Press and Visual Culture in Paris during the Bully Depression: Cahiers d'art, Minotaure, and Verve," Visual Resources: An International Journal of Documentation (2013) 29#3 pp 184-215.

- ^ Anne Latournerie, Petite histoire des batailles du droit d'auteur Archived 15 April 2008 at the Wayback Car, Multitudes north°five, May 2001 (in French)

- ^ Julian Jackson, The Popular Front in France: Defending Democracy, 1934–1938 (1988); Daniel Brower, The New Jacobins: The French Communist Party and the Popular Front (1968)

- ^ Jessica Wardhaugh, "Fighting for the Unknown Soldier: The Contested Territory of the French Nation in 1934–1938," Modern and Contemporary France (2007) 15#ii pp 185-201.

- ^ Susan B. Whitney, "Embracing the status quo: French communists, young women and the popular front," Periodical of Social History (1996) thirty#1 pp 29-43, in JSTOR Archived four March 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Anthony Carter (2011). Motor Racing: The Pursuit of Victory 1930-1962. Veloce Publishing Ltd. pp. sixteen–18. ISBN9781845842796.

- ^ Martin Thomas, The French empire between the wars: imperialism, politics and society (2005)

- ^ Jackson, Pop Front in French republic: Defending Commonwealth 1934–1938 (1988), pp 172, 215, 278-87, quotation on page 287.

- ^ Philippe Bernard and Henri Dubief (1988). The Decline of the Tertiary Republic, 1914-1938. Cambridge UP. p. 328. ISBN9780521358545.

- ^ Wall, Irwin M. (1987). "Teaching the Popular Forepart". History Teacher. 20 (3): 361–378. doi:10.2307/493125. JSTOR 493125.

- ^ Paul Hayes (2002). Themes in Modern European History 1890-1945. Routledge. p. 215. ISBN9781134897230.

- ^ Joseph Bergin (2015). A History of France. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 238. ISBN9781137339065.

- ^ Charles Sowerwine, France since 1870: Civilisation, Gild and the Making of the Commonwealth (2009) p 148

- ^ Colton, Joel (1968). Léon Blum, Humanist in Politics. .

- ^ Lacouture, Jean (1982). Léon Blum .

- ^ Gruber, Helmut (1986). Léon Blum, French Socialism, and the Pop Front: A Case of Internal Contradictions.

- ^ James F. McMillan, Twentieth-Century France: Politics and Society in France 1898–1991 (2009) p 116

- ^ Greene, Nathanael (1969). The French Socialist Party in the Popular Front Era.

- ^ Larmour, Peter (1964). The French Radical Political party in the 1930s.

- ^ Allen Douglas (1992). From Fascism to Libertarian Communism: Georges Valois Against the Third Commonwealth. U of California Press. p. 196. ISBN9780520912090.

- ^ Brower, Daniel (1968). The New Jacobins: The French Communist Political party and the Popular Front .

- ^ Kenneth Mouré (2002). Managing the Franc Poincaré: Economic Understanding and Political Constraint in French Budgetary Policy, 1928-1936. Cambridge UP. pp. 270–72. ISBN9780521522847.

- ^ McMillan, Twentieth-Century French republic: Politics and Society in France 1898–1991 (2009) pp 115-xvi

- ^ J.P.T. Bury, France, 1814–1940 (1949) pp. 285-88

- ^ García, Hugo, Mercedes Yusta, Xavier Tabet, and Cristina Clímaco, eds. Rethinking Antifascism: History, Memory and Politics, 1922 to the Present. Berghahn Books, 2016, pp.53-54

Further reading [edit]

- Andrew, Dudley and Steven Ungar. Pop Front Paris and the Poetics of Culture (Harvard UP, 2005).

- Auboin, Roger. "The Blum Experiment," International Diplomacy (1937) 16#4 pp. 499–517 in JSTOR

- Birnbaum, Pierre (2015). Léon Blum: Prime Government minister, Socialist, Zionist. Yale Up. p. 74. ISBN9780300213737. , new scholarly biography online review

- Brower, Daniel. The New Jacobins: The French Communist Party and the Popular Front (1968)

- Bulaitis, John. Communism in Rural France: French Agricultural Workers and the Popular Front (London, IB Tauris, 2008).

- Codding Jr., George A., and William Safranby. Ideology and Politics: The Socialist Party of France (1979)

- Colton, Joel. "Léon Blum and the French Socialists equally a regime party." Journal of Politics xv#4 (1953): 517–543. in JSTOR

- Colton, Joel. Leon Blum: Humanist in Politics (1987), scholarly biography excerpt and text search

- Colton, Joel. "Politics and Economic science in the 1930s: The Balance Sheets of the 'Blum New Deal'." in From the Ancien Regime to the Popular Front, edited by Charles K. Warner (1969), pp 181–208.

- Dalby, Louise Elliott. Leon Blum: Evolution of a Socialist (1963) online

- Fenby, Jonathan. "The Republic of Broken Dreams" History Toda (Nov 2016) 66#xi pp 27–31; Pop history.

- Fitch, Mattie Amanda. "The People, the Workers, and the Nation: Contested Cultural Politics in the French Popular Forepart" (PhD dissertation, Yale University, 2015).

- Greene, Nathanael. The French Socialist Party in the Popular Front end Era (1969)

- Gruber, Helmut. Leon Blum, French Socialism, and the Popular Forepart: A Case of Internal Contradictions (1986).

- Halperin, S. William. "Léon Blum and contemporary French socialism." Journal of Modern History (1946): 241–250. in JSTOR

- Jackson, Julian T., Pop Front end in France: Defending Commonwealth 1934–1938 (Cambridge University Press, 1988)

- Jordan, Nicole. "Léon Blum and Czechoslovakia, 1936–1938." French History 5#1 (1991): 48–73. doi: 10.1093/fh/5.i.48

- Jordan, Nicole. The Pop Front end and Central Europe: The Dilemmas of French Impotence 1918-1940 (Cambridge University Press, 2002)

- Lacouture, Jean. Leon Blum (English edition 1982) online

- Larmour, Peter. The French Radical Party in the 1930s (1964)

- Marcus, John T. French Socialism in the Crisis Years, 1933–1936: Fascism and the French Left (1958) online

- Mitzman, Arthur. "The French Working Class and the Blum Government (1936–37)." International Review of Social History 9#3 (1964) pp: 363–390.

- Nord, Philip. France's New Deal: From the Thirties to the Postwar Era (Princeton Up, 2012).

- Torigian, Michael. "The Finish of the Popular Front: The Paris Metal Strike of Spring 1938," French History (1999) thirteen#iv pp 464–491.

- Wall, Irwin Chiliad. "Educational activity the Popular Front," History Teacher, May 1987, Vol. 20 Result 3, pp 361–378 in JSTOR

- Wall, Irwin M. "The Resignation of the Starting time Popular Front Regime of Leon Blum, June 1937." French Historical Studies (1970): 538–554. in JSTOR

- Wardhaugh, Jessica. "Fighting for the Unknown Soldier: The Contested Territory of the French Nation in 1934–1938," Modern and Contemporary French republic (2007) 15#2 pp 185–201.

- Wardhaugh, Jessica. In Pursuit of the People: Political Civilization in France, 1934-nine (Springer, 2008).

- Weber, Eugen. The Hollow Years: French republic in the 1930s (1996) esp pp 147–81

External links [edit]

- "The Popular Front: A Brief but Crucial Period in History", interview with Henri Malberg, translated from "Front end populaire : une période brève, mais capitale", originally published on 18 Apr 2006 in 50'Humanité

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Popular_Front_(France)

0 Response to "Greene the Union Show Art Front May 1936"

Postar um comentário